Three Stories from the Arapaho

April 17, 2023

Oftentimes the origin of a high school’s name is given no real thought or meaning because oftentimes, there is no real meaning behind it. Cherry Creek, Littleton, Vista–not necessarily much weight there. However, Arapahoe High school can be excluded from the list of baseless titles. Arapahoe is the name of a Native American nation. That raises the question, how does it happen that a school’s mascot is a group of people?

The story goes that in the ‘60s, there were some school board members who were building a new school and decided to name it “Arapaho”. It was an idea they surely did not give serious consideration to, proved by the fact the board members drew up a caricature for the mascot. A caricature who is not Arapaho but actually (as was pointed out later on by the Arapaho people) a mascot sporting Pawnee garb, an enemy tribe.

It wasn’t until the ‘90s that Ron Booth, who had been Principal since the ‘80s drove to the Wind River Reservation seeking permission from the Arapaho people to use their name and likeness. It was after much deliberation and questioning why nobody had asked them sooner, that the Arapaho elders and leaders did give their blessing.

This story of an American institution using pieces of Native American tribes in ways the institution doesn’t itself grasp is not an occurrence isolated to Arapahoe High school history. It can be extended to the history and the very use of American land itself.

After that blessing was given a deal was made: one year the tribe would visit the school and the next year the school would visit the tribe. And so a relationship began.

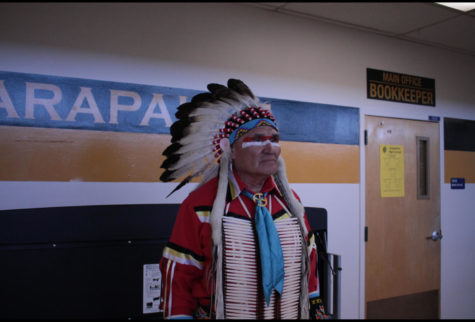

Yet like everything else good in the world, that relationship was interrupted by a certain world wide pandemic. So this year, 2023, was the first time in five years that a group of Arapaho people drove eight hours to visit the school named after them.

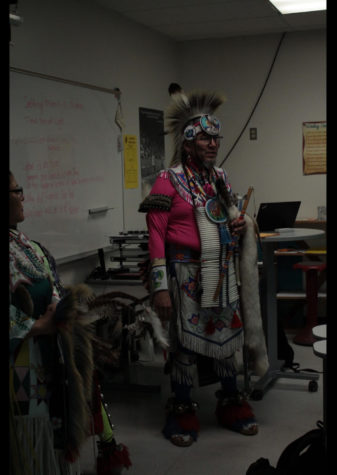

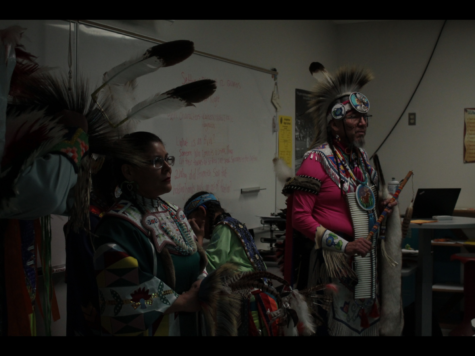

They came to share something of their culture and lives. They came to hold a miniature Powwow and drum circle. But most importantly they came to answer questions, if you would ask that is.

I did just that. I asked many questions and met many people whose words each speak volumes of beauty and history.

Within these conversations I had, I found three stories. They each tell personal, individual pieces of the modern Native American lives that together connect with a greater world of history that has not yet been recorded.

Storytelling is a large part of Arapaho culture. It is by putting the questions answered and the stories shared with me into that format that they are best told and best listened to.

Story One: Killed by a White Man

“I could be totally honest with you, my grandmother, she was murdered by a white man.”

This is a woman named Lucy speaking as she stood with two other women, each in their own traditional Powwow outfits and each a member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe.

Lucy held a film of tears between me and her eyes. She had not said much to me before she told me this.

“My Grandmother worked for the trading post and the owner’s son took it upon himself to- he had an altercation with my Grandmother. She refused to go to work because her baby was sick. And you know what, he backhanded her. She stood only about 4’ 11”, ‘hundred pounds, he backhanded her so hard that it broke her neck. This is a true story.”

“My mother was only 18 months old. And when her grandmother came to check on her, her daughter was on the floor dead and her granddaughter was down there, that was my mom.”

“And so I never had a Grandmother growing up. My mom’s mom was stolen from her. Her Grandmother raised her but she [was] never raised to think any differently of the non-native. You know, they’re not all bad, but we couldn’t go back in history and change that.”

“Our families are very special to us and I just wanted to share that with you.”

This murder happened only two generations ago.

A woman on the far right named Randy spoke to me straight. “There was a point where the American government tried to kill the Indians.”

“Our children were forced into boarding schools where their hair was cut, their clothes were taken from them. They were prohibited from speaking their language. And if they spoke, they were beaten. This is the story of what happened to our children.”

Randy did not want a reaction from me or even an apology, but she needed me to know that this is the truth.

What is also the truth (maybe the greater truth) is that the American government did not succeed in “killing the Indians” as Randy said.

“Here we are today, still living our culture, still holding onto our language. We have jobs and we go to school because we need to eat, we are no longer able to hunt in the way that we once were. But we still survive and still try to enjoy what there is from both cultures.”

“Live humbly, care for one another, have respect for Mother Earth. Try to live life without prejudice, keep an open mind to our native people because we have so many struggles at home. Our young people are so lost, they don’t feel there is a future. Just live life in harmony.”

Story Two: The Brown Family

“We have our different bloodlines as part of our family line. My grandpa was one of our old chiefs, Chief Lone Bear. That’s where we get our last name. Our last name is Brown, but our original, traditional last name before it was Brown, was Lone Bear.”

This is Kenny Senior introducing his family.

“My name is Kenny Brown Senior.”

He is the father of the Brown family. It’s a family of seven (though only five were present). Next to Kenny was his wife Cheryl and fanned out beside her, their daughter Stephine, son Kenny Jr and the youngest Tristan.

The Brown family were all dressed in their ceremonial Powwow outfits. They sported these for a Q&A style conversation with a classroom of high school students.

Cheryl next introduced herself, specifying how she is not actually Arapaho, but Navajo. “I was part of some of the very first generations, 1981, that [were] in the program [that] first had the Navajo immersion school.”

Cheryl and her daughter Stephine wore Fancy Shawl dancer style outfits. “This one was gifted to me when I was very young, I was only six I believe.”

Kenny Sr. pointed to Tristian. “For me and my youngest boy we’re wearing the Chicken Dance style outfit.” He explained, “A lot of this stuff takes time, stitch after stitch.”

These clothes aren’t the folded in the drawer ‘which one should I wear today?’ type clothes. Cheryl doesn’t exactly go grocery shopping in her fancy shawl. Kenny emphasized that, “–when we walked in we had normal regular clothes, sweats, whatever.”

These outfits are occasional, special, they are for Powwows. To understand their significance you need to understand what exactly a Powwow is. In his fashion, Kenny explained.

“Back in the day, a lot of tribes found a meeting spot and they would all come together. It was a place to gather, talk. Different tribes would come from their area, they would bring their dancers, they would say what they saw on this side of the mountain. And you would have the Arapaho people or the Sioux people and they would come, they would say, ‘this is our style,’ and that’s how it came to be.”

“Then they came up with that name, Powwow. Now days, it’s kinda about the almighty dollar and back in the day it wasn’t. But you know, we’re all a part of that society now.”

We are all a part of that society now, the native and non-native, we all live in this same society. But we don’t all live with the same rules. Historically it’s no secret that the U.S government chronically swindles Native American people. Modern times can’t assume they are excused from the barbaric dealings of injustice.

I asked Kenny, frankly, if he has seen the U.S government change.

“They still haven’t—if you really think about it. We’re slowly starting to get recognized. We have this school [Arapahoe] who’s starting to see that there’s something good here. But yet we try to do something as far as legal stuff and they still look upon us as ‘those Indians’.”

“In the past it was, ‘those are Indians don’t talk to them’, that’s part of the stereotype that is always portrayed. In movies you see the warriors going in and killing people, taking scalps. All of a sudden, everybody assumes we’re like that, we’re angry people. That’s not true.”

“A lot of the times when we go to Q&As like this, some of the questions we get are, ‘are we still livin’ in teepees?’ and ‘where do we go to the bathroom?’, stuff like that.”

“They [the government] don’t see us as natives to this cultural land, this land that was ours. It’s hard because we have to go to the government for things but we don’t always get’em.”

“Right now it’s just one school. We need the colleges. We need the big, big, things that open up for the people, for our people.”

“So you know they haven’t changed. It may seem like it has but in reality… it hasn’t.”

There is no pat on the back in his words, just an uncomfortable space left for the kids in the room to feel suddenly the large malnourished gap between all the people who indeed share a society.

“Just be open to the teachings because that’s the only thing we have to share, our teaching.”

Story Three: We are Here to Laugh With You

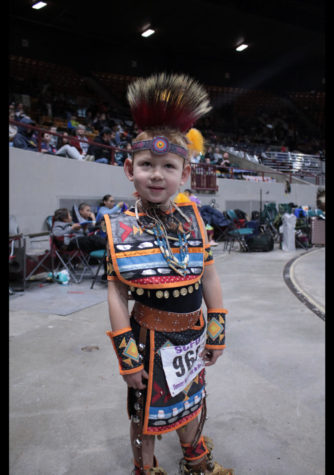

Arapahoe High School was only a pit stop on the trip the tribe was taking. One day after their visit I followed the Arapaho to their greater destination, the Denver March Powwow. It’s one of the largest Powwows on the western side of the country and it marks the beginning of Powwow season which lasts until fall.

The Denver Powwow is a supermarket of furs and clothes and art in the many intricate subculture styles of the east, west, desert and plains tribes (to only name a few). I went to witness and absorb all of it.

Sitting in the Colosseum I could see that there were a few hundred Powwow dancers stacked in dense lines outside. They waited to march into the arena in groups separated by dance style. Before they could march, a man who introduced himself as the MC of the Denver March Powwow wished to introduce the spirit for the day.

“I’m not saying [that] what we do and the drums are going to cure you, I can’t give you that guarantee.”

“If you take anything away from our people, we’re spiritual, we have ceremony, we pray. Our ‘savagery’ is what the United States called us, savages. French call us savage. If you’re Johnny Depp, that’s a cologne.”

“But in all of these things that we do, we come together in prayer, we come together to laugh, to joke, we come together as a people who dance.”

“We’re here to share wisdom. We’re here to share the journey that we’ve taken as human beings in life. The journey of heartbreak, the journey of finding love, the journey of finding friendship. Not Indian, not white, not any color under the sun.”

“For those of you that don’t understand, as Indian people we believe that everything has a power and a way. Water, earth, wind, the sun–it has power.”

“They say in our people and in our way, if we don’t laugh with you, that means we don’t care for you. Pretty simple. We respect you and we honor you with our humor.”

“All of us in this room have gone through historic trauma. We’ve gone through historic trauma that has been thrust upon us by the American government, making us “good citizens”. So white people that have joined us–for the moment that we’re in this Colosseum it’s the sovereign nation of indigenous people.”

“Also, the elephant in the room. My ancestors killed your ancestors, your ancestors killed my ancestors. Okay. I said it. It’s done. Let it go.”

The Story of Now

Last year in the state of Colorado a law was enacted which required that all existing schools remove any mascot of a Native American tribe and imposed a “fine of $25,000 per month for each month” for any school that had not removed the mascot completely. It was passed in the spirit of overdue respect.

It is the relationship Arapahoe High School has with the Arapho people that exempted the school from that law.

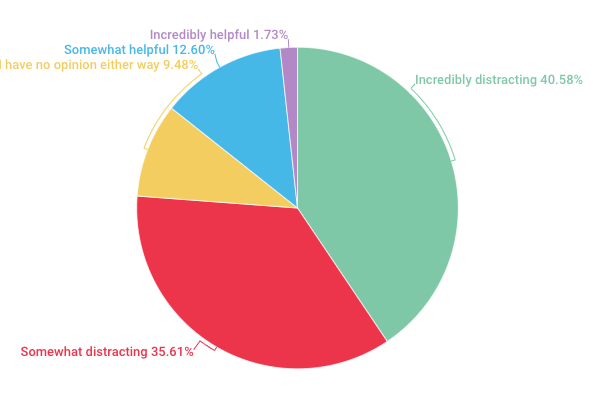

The Arapaho visit and the Powwow assembly they put on was the only time in my four years of high school I ended up feeling glad I had gone to an assembly, more than that, the only time I felt wiser afterwards.

That day and the Denver March Powwow brought a shared air that something meaningful had happened–a something which is unaccomplished in schools and rare nearly everywhere–it is the bridging of two cultures.

Arapahoe High school has done a good thing.

The pure brilliance of the bond between the Arapaho Tribe and the body of a high school accentuates the lack of such bonds in everything else.

Though the people in high school may have not had surface level connections with the strangers from the reservation, sharing conversations proved to level all misunderstanding and separation.

“Be open to the teachings because that’s the only thing we have to share, our teaching.”